|

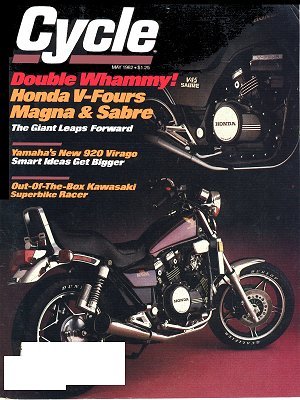

Cycle - May 1982 |

|

|

HONDA |

Honda has cut its V-four two ways. The Magna is the New four with an appearance bias; the Sabre The one faithful to function. The Magna adheres to the shape that most of all sells. |

This is the motorcycle everybody else was afraid Honda might

build someday. Those who weren't worried should have been, and probably are now.

Honda would not have built this motorcycle do five years ago, nor given it a

proper name. Welcome to 1982.

Honda's new 750. or V45 it you prefer, proves

that the era oft the Universal Japanese Motorcycle, given formal definition in

this magazine years ago, is an era in passing. Honda could have built a third

generation UJM, a successor to the first CB750 series (1969-1978) and the second

(1979-to whenever), but did not. To be successful in the 1980s, a manufacturer

must produce something that is new and is perceived as new. Yamaha understood

this proposition first: designers dressed up an old motorcycle in new and

different clothes, the Yamaha XS650 twin, and finally created a new motorcycle

in different clothes, the 750 Virago.

Honda engineers started with empty drafting tables and blood in their

eye; the result is new, staggeringly new. You want a freshly minted engine, a

copy of nothing and similar to nothing before? Well, have this Vee-four with

four overhead camshafts, 16 valves, water cooling six speeds and shaft drive.

You'd have to be blind and deaf to miss the newness of this motorcycle. You want

a styling motif in cruiser mode, Milwaukee esque, something with a dense,

industrial look in the engine compartment, something that looks like it could

repel sledge-hammer blows?

Honda engineers started with empty drafting tables and blood in their

eye; the result is new, staggeringly new. You want a freshly minted engine, a

copy of nothing and similar to nothing before? Well, have this Vee-four with

four overhead camshafts, 16 valves, water cooling six speeds and shaft drive.

You'd have to be blind and deaf to miss the newness of this motorcycle. You want

a styling motif in cruiser mode, Milwaukee esque, something with a dense,

industrial look in the engine compartment, something that looks like it could

repel sledge-hammer blows?

At one time Honda might have blushed, hesitating

to pursue glitz and fashion and the vagaries thereof. Today Honda invites you to

try the route to the Midwest via Asaka, Japan. Now the Motorcycle Engineering

Company has even found a toughie-boy name for this mean-ish, Vee-four Mo'Sickle:

Magna It takes a hidden, auxiliary fuel tank and a fuel pump to have both

reasonable gas capacify and a main gas tank in the cruiser style and size. So be

it: then the Magna has two tanks and one fuel pump. Eeeek: Form dictating

function, right? Not entirely. Did anyone ever complain that the Gold Wing has a

fuel pump and tank buried in the "wrong" place, and a falsie-tank in front of

the saddle? The point is this: when the engineering department begins by tossing

out the UJM concept and designs a completely new engine and motorcycle, then

form becomes just another set of engineering issues that the department deals

with.

The Magna is Honda's ultimate weapon in market warfare. Here's a

motorcycle that retails for $3298, barely more expensive than premium 550s.

Potentially these V45s~Magna and Sabre could cut a broad swath through

motorcycling, from the 550 level upward. The Sabre offers new with a

functional bias, and the Magna new with an appearance bias. If the functional

purist didn't have the Sabre option, he'd be tempted to buy a Magna for the

engine alone, and then remake the rest of the motorcycle to suit.

The Magna is Honda's ultimate weapon in market warfare. Here's a

motorcycle that retails for $3298, barely more expensive than premium 550s.

Potentially these V45s~Magna and Sabre could cut a broad swath through

motorcycling, from the 550 level upward. The Sabre offers new with a

functional bias, and the Magna new with an appearance bias. If the functional

purist didn't have the Sabre option, he'd be tempted to buy a Magna for the

engine alone, and then remake the rest of the motorcycle to suit.

That would

be difficult. Because, while Honda used the same engine/drive train package for

the Sabre and Magna, the motorcycles are very different machines. In the Magna,

the cruiser seating position benefits from the narrow engine, a bit more than 16

inches wide at the pegs. This means the footpegs can be moved far forward; and,

in fact, the Magna has the most radically forward-positioned pegs of any Honda.

With most transverse four-cylinder engines, the rider would have his feet

splayed out and his toes in the alternator cover. The Magna's rear-bank cylinder

head (9.0 inches across) allows the tank to stay narrow and still cover the

mechanicals below.

In both the Magna and Sabre, low saddle height was an important

objective. The V-fours' rear-bank cam covers come apart in two sections; this is

a consequence of dropping the upper frame rails as low as possible, running them

along the top of the engine. And in the V-four frames, the left-side

engine-cradles unbolt to permit side excavation of the engines.

In both the Magna and Sabre, low saddle height was an important

objective. The V-fours' rear-bank cam covers come apart in two sections; this is

a consequence of dropping the upper frame rails as low as possible, running them

along the top of the engine. And in the V-four frames, the left-side

engine-cradles unbolt to permit side excavation of the engines.

With a saddle

height under 30 inches, the Magna is a real low-rider. In this, the twin-shock

rear suspension aids; a single shock positioned under the seat would, with the

inclusion of other components, require more seat elevation to get everything in

and under. Among these components is the under-saddle gas tank, which is the

second part of an interconnected fuel system. An electric fuel pump draws from

the bottom of the lower tank to feed the carburetors. Thus, styling

considerations (such as tank shape) and engineering objectives (such as low

saddle height) were served by building a twin-shocker.

From the broad, flat

seat, the rider reaches out to the handlebar, the grips of which angle back,

down and outward, positioning the rider's hands just forward of a vertical line

rising from the footpegs. Now that's forward pegs. The Magna gas tank appears

smaller and narrower than the Sabre's; smaller it is, because the air filter

must, unlike the Sabre's, live under the tank. But, curiously, the

Lower, 1-gallon fuel tank interconnects with main upper tank. Fuel pump draws from lower tanks bottom. Fuel system has straight on-off petcock: no reserve position. Under seat compactness keeps seat height low.  Magna's air cleaner fits under the tank between the frame tubes. Undressed bike shows all available space occupied. |

Magna tank is wider and lower than the Sabre's at

knee-contact points.

The low saddle, forward pegs and erect riding position

allow short riders to get both feet planted flat on the ground at stops, where

their legs will be behind the pegs. That's terrific for stoplight trollers on

the avenue; the ergonomics are less splendid outside city limits.

The forward

pegs and the resulting riding position conspire to make the Magna a short-hop

motorcycle, regardless of how cushy the suspension might be. Fifty miles of

freeway riding is acceptable; 150 miles of varied riding in a single sitting

tested our riders' limits. One tester always wore his Gold Belt when he rode the

Magna. Peg location is the most objectionable single feature because it strains

the back by forcing the spine to support upper-body weight; arms, shoulders and

hands bear no stationary load at all. Wind speed aggravates the problem by

making the rider pull into the bar.

Because they are less ergonomically

successful than standard motorcycles, cruiser style bikes actually fit a narrow

range of riders. Parked in a showroom, at rest, they feel reasonably comfortable

to everyone. In actual road use, however, an individual rider's physical

characteristics explain much of his reaction to the motorcycle's comfort. Riders

who are large and overweight, or who are well over six feet tall, or who have

relatively long legs and short torsos, or who have back problems from age or

injury are, in general, not good candidates for the sit-straight school of

ergonomics. But shorter riders, riders with relatively long torsos and abort

legs and with backs in good condition show less sensitivity to the riding

position of motorcycles like the Magna. Bringing back real test rides (don't you

wish) would probably help an enormous number of riders decide whether a

particular motorcycle style is well suited to their physical characteristics and

emotional preferences.

Honda matched the Magna's suspension to its riding

position; compared with the Sabre's, both are mediocre. They're a match in

another way The sit-up riding position cries out for a soft rear suspension to

minimize road shocks administered to the rider's spine. That Honda has done, hut

the choices aren't easy here. There are trade-offs. The low saddle height means

that the rear suspension can't have much travel, and the ever-popular shaft

drive guarantees lots of rear wheel sprung weight, which is always difficult to

control; matters are complicated by a final-drive system that tries to extend

the suspension under power and settles down on trailing throttle. Makers have

therefore produced shaft-drive motorcycles that cluster around two poles. At one

pole are bikes with firm to harsh rear suspensions that behave well under hard

riding that tests handling; at the other pole are bikes that have soft, pleasant

rides on the freeway, and get unruly under backroad pressure.

Honda engineers

seem to have concluded that the Magna should be boulevard and freeway cushy:

soft springs and light damping, and nothing further. The rear suspension units,

while trick-looking with their remote reservoirs, have no damping adjustment.

Five-position spring preload sums up the shock absorbers' adjustability.

The

rear suspension delivers a smooth and compliant ride around town with little

preload (one or two). On straight highways at speed, preload to the third or

fourth level is required to cancel out a floaty sensation over bumps,

reminiscent of traditional American luxury cars. Still, the soft. short-travel

rear suspension bottoms out over medium potholes, or by adding a passenger.

While it has reasonable ground clearance. the Magna resists sporty-type riding

over backroads. With little preload. the bike feels rubbery and vague in corners

over bumps and on trailing throttle: a lot of preload helps, but you're working

against the basic suspension decisions made in Japan, there's lust too little

spring, not much travel, not enough damping, and all that sprung weight. The

Magna needs less flash and more substance in the rear suspension units - Fully

adjustable damping, both rebound and compression, and maybe air-assisted

springing, would give owners some latitude to make their own suspension

trade-offs.

The 37mm front fork is likewise calibrated to the Magna's cruiser

role. It's air-assisted fork caps have individual valves in them, and we

experimented with air pressures between 12 arid 22 psi. twelve pounds let the

fork soak up road imperfections; though it didn't quite intercept less severe

pavement irregularities such as slight pavement breaks as well as the fork on

our last test CB1100F. At 12 psi the fork could be bottomed on driveway

entrances. Increased air pressure obviated this bottoming problem without

disturbing the fork's compliance over lane-divider dots.

The Magna's built-in

fork brace should help keep the tubes from twisting under decisive input tram

hard riders at high speeds. making the steering feel very positive and

instantaneous. Both the Sabre and Magna have a greater distance between their

lower triple clamps and axles than the current motorcycle norm. If tying the

sliders together top and bottom reduces any flex-induced stiction, then Honda

has been successful be cause the front fork is very active. Furthermore, the

Magna and Sabre forks have their dual Syntallic bushings both located in the

sliders, rather than one on the tubes and one in the sliders. The new system

keeps the bushings the same distance apart and thus the fork may be a little

more responsive when operating at near full extension. Both bushings bear (and

slide) against steel tubing.

The front fork is TRAC-equipped, Honda's version

of anti-dive, explained in detail in the CB750 Nighthawk test (April, 1982).

Functionally, we like this system on two counts: Since it does nut work off the

master cylinder, the front brake lever never feels spongy: and TRAC produces

more anti-dive effect, we think, than in other contemporary systems.

The

diminished front-end dive encouraged our test riders to use the front double

disc brake harder than normal, thus provoking tire howl. You wouldn't want do

this unless the brakes were progressive and readable. Honda's are. The Magna

employs the now familiar Honda double-piston calipers, elongated pads and

slotted discs. On the Magna the non-adjustable front brake lever seemingly has

little tree play, causing small-handed riders to pull against master-cylinder

pressure with their fingertips, an annoying niggle when wearing winter riding

gloves. Actually the hand position on the Magna bar grip creates this impression

by putting the lever at a greater reach than standard bars do; the amount of

lever free play is just fine. In any event two or three fingers can howl the

wide-footprint 110-90 x 18 Dunlop Qualifier tire. The rear drum brake, built

into the cast rear wheel, is small but works fine. Motorcycling seems over its

compulsion to fit 10 inch discs to rear wheels.

Honda has kissed good-bye to

the composite wheels in favor of cast alloy- primarily a concession to styling

rather than engineering. As a style leader, the Magna must have state-of-fashion

cast wheels. The rim widths (2.50 front: 3.00 rear) indicate that the V-fours

have reached 1982 tire requirements and are prepared for future developments.

Indeed, rim width is a more significant advance here than wheel construction.

After nudging the choke lever

up, turn-lag the key and hitting

the starter button, you'll not question where the greatest technological leap

forward lies in the Magna: the engine. It has a throaty, gutsy flat sound,

something like two Honda 400T twins revving in unison. More amazing is the sheer

volume of this sound. Is it legal? Yes. Decibel meters can't distinguish between

exhaust notes and mechanical noise emanating from engine cases; human ears can.

Quiet the engine with water cooling, silent timing chains and anti-backlash

gears and, presto, you can step up the good sounds, which are clear and present

to the rider at stops, not at speed. While the Sabre treats its rider to a display-panel light show, the

Magna has traditional dial face mechanical drive tachometer and speedometer,

indicator lights and a water-temperature gauge. These lights reside under dark

window panels, and indicators light up the appropriate leg ends marked on the

dark window panels. In shade, readability is fine; in strong, direct sunlight

the lights are almost invisible. A rider might miss the fuel level warning light

during a fast cruise on a sunny day. The light generally winks on at 110 to 120

miles, presumably when the main tank runs dry (2.6 gallons); but should you miss

it for 30 miles, you'll be about 10 miles away from pushing. The Magna has no

reserve tap, only an on off fuel valve located behind the right side-cover.

Another surprise; Filling the gas tank to the brim causes the cap to seep.

While the Sabre treats its rider to a display-panel light show, the

Magna has traditional dial face mechanical drive tachometer and speedometer,

indicator lights and a water-temperature gauge. These lights reside under dark

window panels, and indicators light up the appropriate leg ends marked on the

dark window panels. In shade, readability is fine; in strong, direct sunlight

the lights are almost invisible. A rider might miss the fuel level warning light

during a fast cruise on a sunny day. The light generally winks on at 110 to 120

miles, presumably when the main tank runs dry (2.6 gallons); but should you miss

it for 30 miles, you'll be about 10 miles away from pushing. The Magna has no

reserve tap, only an on off fuel valve located behind the right side-cover.

Another surprise; Filling the gas tank to the brim causes the cap to seep.

The

Magna, a hundred greenbacks cheaper than the Sabre, lacks two

important features of its mate. First, no self-canceling turn signals; second,

no fiber-optic safety cable. We didn't miss the self extinguishing signals; for

our tastes the Sabre signals cycled far too short a time and distance. On the

Magna, we would have preferred the turn-signal indicator lights at the top

rather than the bottom of the instrument panel.

By virtue of the Magna's

looks, we think it's more likely than the Sabre to be ripped off, but the Magna

has only the protection of an ignition key fork lock combination. The Sabre has

a key activated, self contained and independently powered alarm system, into

which plugs the male end of a sheathed cable, normally stowed in its place above

the tool kit. The cable has a closed loop-eye on one end; the rider can lasso a

lightpost and plug the male end into the receptacle beneath the left sidecover.

The sheathed cable has fiber-optic material in its center; if the cable is cut,

a piercing little beeper sounds. The system can't be circumvented. The anti

theft system is neat but the Magna doesn't have it. For Magna owners its an

accessory alarm, lock, and chain, garage or hard to hand combat

Wet weather

riding is no treat with the Magna or the Sabre. The front fenders are useless

for water protection; in all probability they are better than nothing. The

Magna's rear fender is so short if seemingly does little to keep the rear wheel

spray from being pulled up and forward. Our advice to Magna riders who see a

storm ahead, head for shelter.

Day or night, rain or shine, the effortless

way the Magna operates on the far distant side of Legal-Speed is a tribute to

the engine, its mounting system and the sixth overdrive gear. Since the V-four

has perfect primary balance, the only concern might he some secondary vibration

at high engine speeds. Yet this is inconsequential because the engine attaches

to the frame (both Magna and Sabre) with six rubber mounts. four on the

crankcases and two on the rear cylinder head; the mounting system is identical

to that on CB900F bikes, with two kinds of rubber in a collar, the first

controlling radial and the second lateral vibrations. In this way high-frequency

vibrations fail to penetrate to the rolling chassis and rider. Finally, the

engine turns about 4500 rpm at 55 mph in fifth, and sixth drops the revs below

an indicated 4000 rpm.

At the drag strip the Magna recorded an impressive

12.29-second quarter-mile, running through at 109.62 mph; the Sabre cut through

in 12.23 seconds at 108.56 mph. These V-fours surround the Kawasaki KZ750E3 (December 1981), which posted a 12.276-second, 109.22-mph pass at the drag

strip. To date, the Magna is the fastest 750 we've put on the strip, by about

0.4 mph, and the Sabre is the quickest arriving at the quarter's end a

0.046-second nano-blink sooner than the KZ750.

Normally, we'd bubble over

about the raw numbers; the V-fours, however, impress the rider in a completely

different way: the nonchalant almost detached way they make this performance. No

fuss, no busyness, just here's a 12.23 and it wasn't much of a bother --let's he

on our way.

We decided the V-four should he on its way to the dyno, despite

the difficulties created by mating a shaft drive motorcycle to the dyno. Because

the Honda V fours were so radically new and we were so curious about their power

output, we had a special fixture built at the dyno so the V-four could he put on

the pump. We knew that despite differences in the air cleaners and pipes, both V

fours had nearly identical outputs. The Sabre went to the dyno. With the rear

wheel removed, the Sabre's drive shaft turned a special rear axle carrying a

sprocket, which in turn linked to the dyno sprocket by means of a chain. Bear in

mind that the method introduces one more stage between engine and dyno. Though

not tentative, the figures reflect our first experience: only further experience

will demonstrate how completely numbers taken this way can he compared with

others from chain-driven bikes. The V-four's horsepower and torque figures may

he slightly higher than indicated by our charts. Although the Magna and Sabre

are about 20 and 30 pounds heavier, respectively, than the Kawasaki Kz750. the

dragstrip times for all three bikes were practically the same

The V-four

makes a bit more peak horsepower than the K7750 (65.05 vs. 62.10), but it's the

VF750 power spread that's compelling. Where the Kawasaki makes more than 59

horsepower over a 1000-rpm hand, the V-four does so over a 2000-rpm spread.

Upstairs, there's more horsepower under the curve, which helps to explain why

the heavier V-fours could run with the Kawasaki at the strip. The Kawasaki,

however, has marginally better horsepower figures, in general, from 2500 rpm to

6000 rpm. The quickest and fastest Honda CH750F in our record books ran a 12.57

105.01 mph quarter mile, it made the same kind of upper end dyno power as the

V-four, was about as strong down-range, and weighed about 30 more pounds than

the Magna. Figures aside, the Magna and Sabre are strong. The V-four impresses

riders as having a broad, flat and high torque curve and a lot at pull-away

power in sixth gear.

That quality about the V tour makes one wonder whether

Honda has a touring Magna on the drawing boards. Look how the pegs, gearshift

linkage and brake pedal are laid out, and then think about it. Honda could

easily make an alternative tank, seat, bar and footpegs for the Magna, then

upgrade the rear suspension, and create an instant tourer. The Magna's seat, a his and her split level number, corresponds to the

riding position and rear suspension. The riding position drives long-legged

riders back, putting their rumps against or on the rise pocket; it's better for

smaller people. The saddle is broad, flat and soft in the rider's pocket If

feels cushy enough, and with a short rear suspension travel the seat must assume

rider suspension duties. Yet after 100 miles or so, a rider feels as if he's

compressed the foam even though he hasn't; it's just that fatigue and bun-burn

make him aware of the saddle's flatness and the stepped ride. For any one rider,

the ergonomic relationships and the saddle construction dictate a single seating

position. From that pocket, the rider can get little fore-aft movement, and the

rear footpegs are too far rearward to give the rider any alternate positioning.

Like the Sabre, the Magna could use some more seat work for those riders who

want to ride more than a 100 miles in a stretch.

The Magna's seat, a his and her split level number, corresponds to the

riding position and rear suspension. The riding position drives long-legged

riders back, putting their rumps against or on the rise pocket; it's better for

smaller people. The saddle is broad, flat and soft in the rider's pocket If

feels cushy enough, and with a short rear suspension travel the seat must assume

rider suspension duties. Yet after 100 miles or so, a rider feels as if he's

compressed the foam even though he hasn't; it's just that fatigue and bun-burn

make him aware of the saddle's flatness and the stepped ride. For any one rider,

the ergonomic relationships and the saddle construction dictate a single seating

position. From that pocket, the rider can get little fore-aft movement, and the

rear footpegs are too far rearward to give the rider any alternate positioning.

Like the Sabre, the Magna could use some more seat work for those riders who

want to ride more than a 100 miles in a stretch.

Again like the Sabre, the

Magna throws some heat back on the rider from the radiator. California winter

conditions were cool enough that we couldn't quite determine how objectionable

the heat throw-oft might be. A couple of 85 degree days indicated that the

outside temperature combined with radiator throw-off and radiant heat from the

rear cylinder head would warm the Sabre rider's legs and thighs to tolerable

limits. Clipping along on the Sabre on a 90-degree after noon might be

unpleasant. The Magna, with its wider gas tank and different riding position,

doesn't have the problem to the same degree as the Sabre In part, the rider's

legs are farther away from the engine; also, the Magna's riding position

encourages lower highway speeds.

We'd fake a fair amount of heat to get this

engine; it's that much a functional marvel in other ways. In functional terms

the Magna is compromised compared with the Sabre. Pure-blood sporting riders

will proceed directly to the Sabre without so much as a look at the Magna. But

guys who want that engine in a motorcycle with styling bias will gravitate to

the Magna. Honda figures the Magna customers will outnumber Sabre-types three or

four to one. These V-fours signal a giant step forward; they represent a

breath-stopping escalation of techno warfare in the motorcycle market; they

portend the arrival of a whole new generation of Honda street motorcycles; and

the Magna, especially, announces that in the future everyone will have to sell

style and super tech together.